Held Back

Why Austin's Schools Aren't Working

For Students Of Color

There's a problem in public education that no educator, researcher or lawmaker seems to be able to solve.

In most urban school districts across the country, including the Austin Independent School District, black and Latino students don't perform as well on standardized tests as their white and Asian peers.

This is called an achievement gap, and it's something people in the education world have been talking about since the 1960s. School districts and state legislatures have poured billions of dollars into trying to improve test scores of minority students. Researchers have conducted numerous studies.

But decades later, the problem still exists. In AISD last school year, less than a third of black students and around 40 percent of Latino students passed state reading exams. That's compared to nearly 80 percent of white and Asian students in the district.

The AISD school board and superintendent made it a priority in 2017 to help minority students do better.

But it's a challenging goal. Students who are falling behind academically often face other obstacles outside the classroom: homelessness, food insecurity, emotional problems, lack of familial support. So much affects how students do once they get to school.

There's a fierce debate on what it takes to close this gap, and it's currently playing out in the boardroom and classrooms of AISD.

'They Expect Us To Be Superheroes'

When we're talking about the achievement gap, we're talking about test scores. Here in Texas, every student takes the STAAR test, a state exam, every year in third through eighth grade. Educators, lawmakers, state agencies and researchers use scores from this test to compare students within the city and around the state.

That can be controversial: Many people say there is more to determining a student's success, but tests are the only common measure there is.

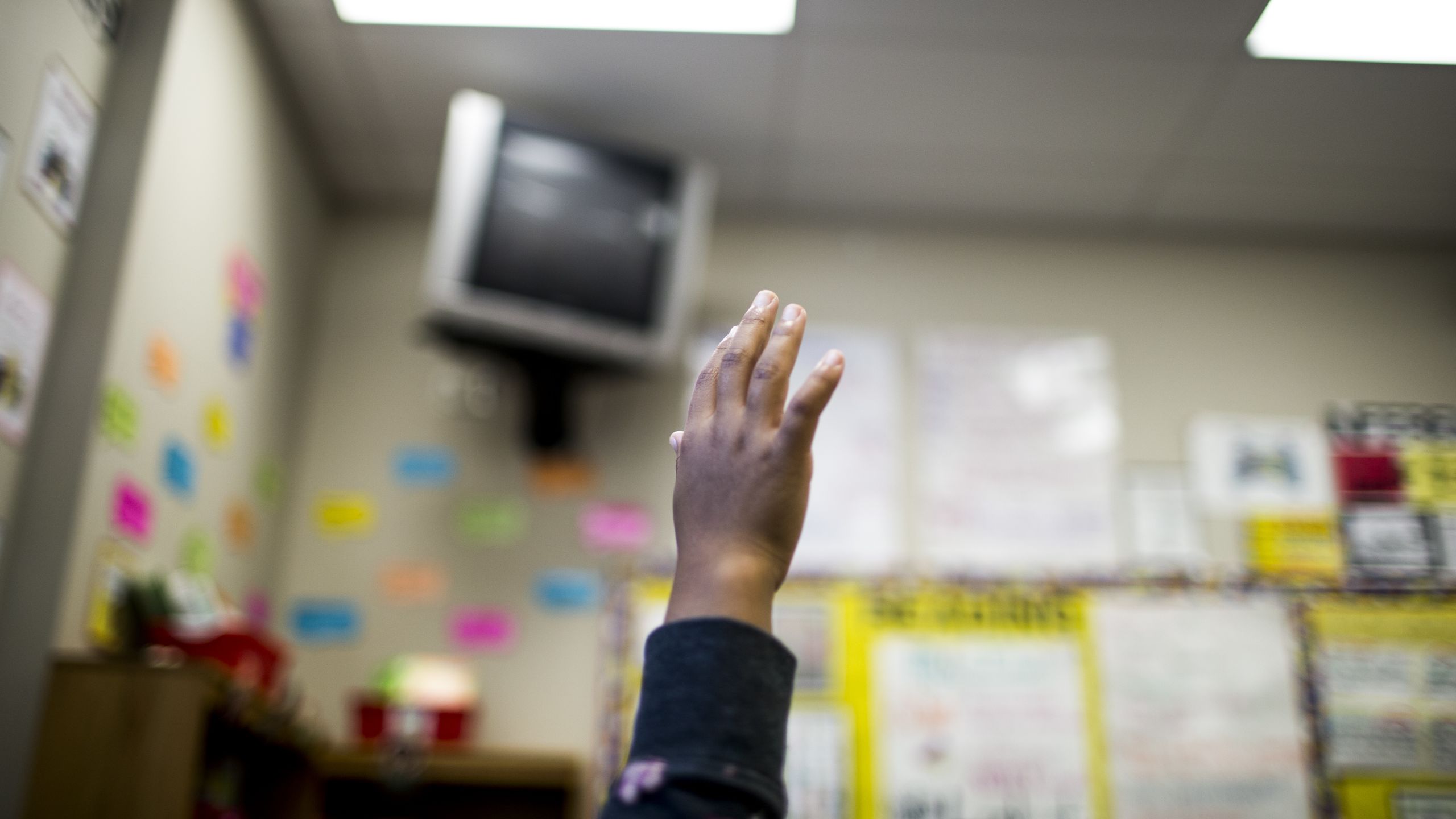

Savanna Wilson, a teacher at Overton Elementary in Northeast Austin, knows the emphasis on – and drawbacks of – the STAAR test.

Savanna Wilson, who teaches fourth grade at Overton Elementary School in East Austin, says she feels overwhelmed by the call to close the achievement gap. | Gabriel C. Pérez/KUT

Savanna Wilson, who teaches fourth grade at Overton Elementary School in East Austin, says she feels overwhelmed by the call to close the achievement gap. | Gabriel C. Pérez/KUT

Last year, only a third of the 557 students met grade level in all subjects, compared to 52 percent in the district overall. Nearly 65 percent of Overton students were English-language learners, and 93 percent came from low-income households. Only a handful of them were white.

A year ago, she stood in the middle of her fourth-grade classroom, breaking the students into small groups for a language arts lesson.

To prepare for an upcoming STAAR test, Wilson had the students practice reading comprehension. The kids in one group didn't understand the phrase "well known," so she walked them through some examples.

"Let's think of Beyonce; she's well known," Wilson said. "What's another word for that?"

"Famous," a student responded.

Helping students master this lesson on synonyms is something that excites Wilson as a teacher. But often, her job is about more than just lessons: She needs to address students' basic needs.

"I have a few that are technically homeless," she said. "So they might not have food or breakfast."

"There's so many challenges for children today. Period. I don't think we'll ever be able to close the gap."

Another challenge is kids transferring in and out of the school, which disrupts their education. One student in her class that day had been there less than a month. There's so much out of her hands, she said, she often feels overwhelmed by the goal to close the achievement gap.

"As far as the gap, it's just, I don't know what they expect us to do," she said. "But it's rough on the teachers. They expect us to be superheroes."

Wilson said some students aren't reading or doing math on a fourth-grade level, so she does what she can to help them improve. She said she isn't sure every teacher can completely prepare students who are behind for the STAAR tests.

"I don't think that everyone is capable of doing that," she said. "It's not realistic. There's so many challenges for children today. Period. I don't think we'll ever be able to close the gap."

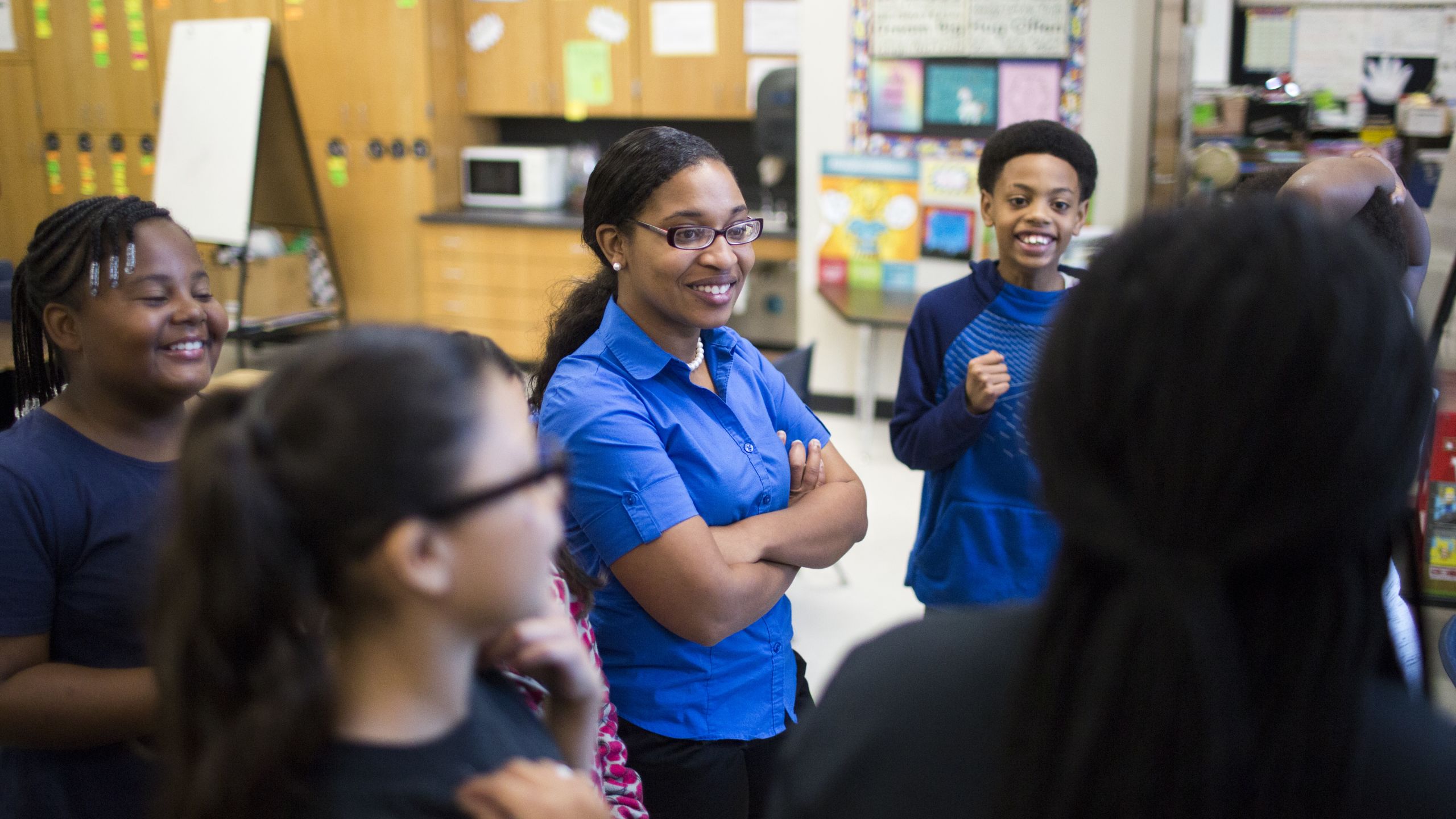

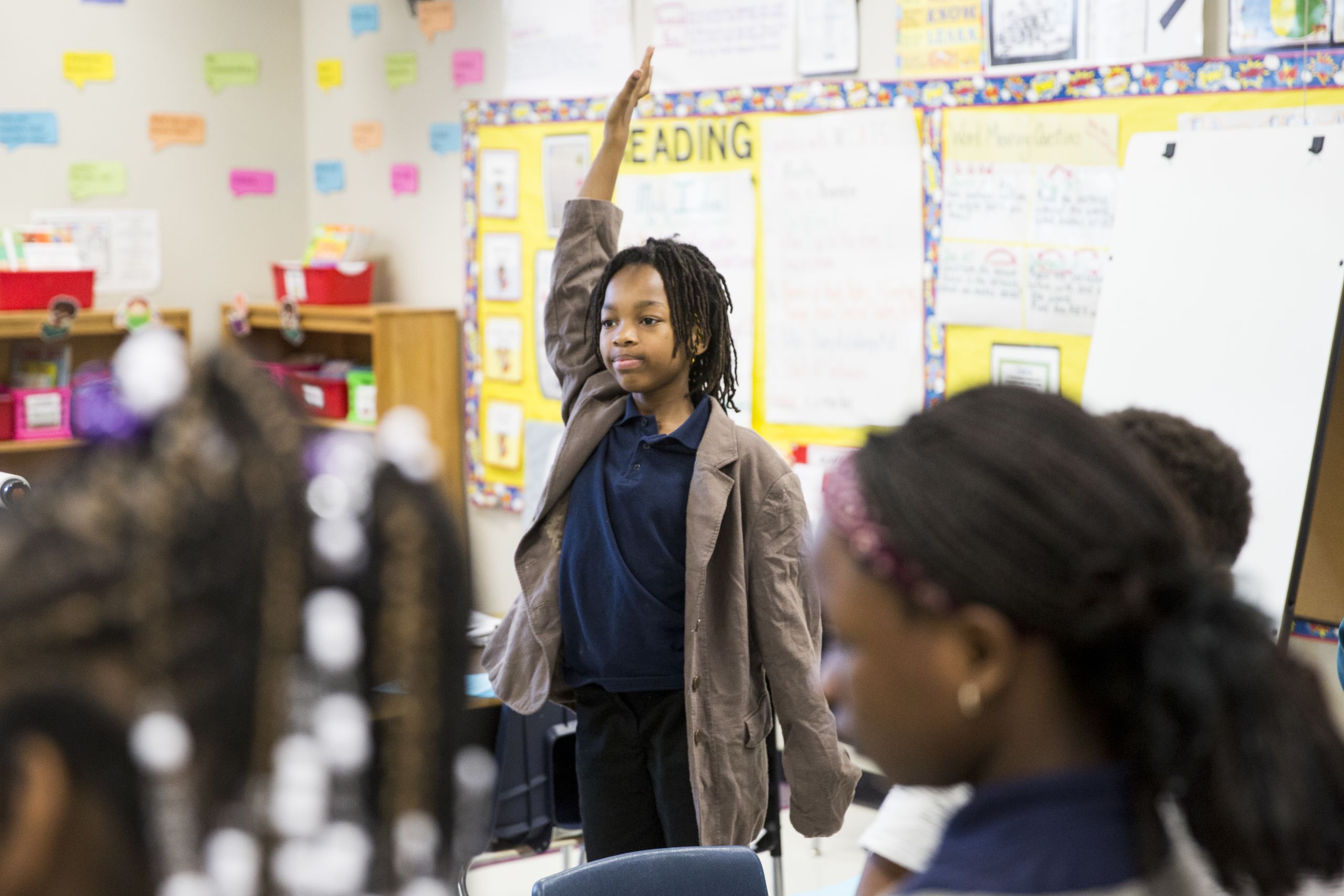

Students Melvin McPherson, Anthony Phagans, Mikeya Dearly and Tshala Mukuba raise their hands in Savanna Wilson's class at Overton Elementary School. | Gabriel C. Pérez

Students Melvin McPherson, Anthony Phagans, Mikeya Dearly and Tshala Mukuba raise their hands in Savanna Wilson's class at Overton Elementary School. | Gabriel C. Pérez

Savannah Loggins

Savannah Loggins

Anthony Phagans

Anthony Phagans

Jayden Whitley

Jayden Whitley

Alex Smith and Zander Nowell, freshman English teachers at LBJ High School, saw this firsthand last school year.

It was their first year teaching at the school, where Overton students land. They designed the curriculum together, picking books, poetry and articles written by people of color, Smith said, so the students would see themselves reflected.

"We read a book by MK Asante; we read a lot of Ta-Nehisi Coates – because I'm a bit obsessed," Smith said. "We did ‘The Purpose of Education' by Martin Luther King Jr."

While students were often excited about the books, Nowell said, they couldn't always read them.

"I'd say somewhere between a third and a half are not reading on grade level," he said.

By this point, students are supposed to be analyzing books and articles, not learning the basics. It can be difficult because high school teachers aren't always trained in the science of reading instruction.

If a student struggles for a few weeks, and a teacher or parent can’t intervene fast enough, the child could quickly start to fall behind. And before you know it, the student is not reading on grade level. Multiply this situation by a couple dozen kids in one classroom, hundreds of kids in a neighborhood, and thousands across the city, and it's easy to see how this problem exists.

Research shows if a student doesn't learn to read by third grade, it's much harder to catch up in later grades. So if schools want to close the achievement gap, reading is the place to start.

One principal in Austin saw that teachers needed a plan to help black and Latino students who were behind. Armed with the research on reading, Blaine Helwig tried to create a solution.

A Culture Of Reading And Repetition

Graham Elementary in Northeast Austin looks like many schools in the district: Its students are mostly Latino or black, more than half are learning English, and almost all of them come from low-income families. These are some of the major factors that contribute to an achievement gap.

Like students in schools with similar demographics, Graham students were not doing well on those state tests before 2007.

Graham Elementary School's test scores improved dramatically after Blaine Helwig became principal. | Gabriel C. Pérez

Graham Elementary School's test scores improved dramatically after Blaine Helwig became principal. | Gabriel C. Pérez

That changed after Blaine Helwig became principal.

Reading specialist Gloria Reyes said his arrival brought a different feel to the school. The previous principal was "touchy feely," she said, and professional development sessions often included team building.

"Blaine was like – 'You know, I'm not into that. I'm into the kids,'" she said. "'So you're just going to get something different. This is where we are, this is where we need to be, these are the plans to get there.' He definitely had a plan scheduled out."

One of Helwig's plans was to improve students' reading. In the few years before he started, the passing rate for the school on the STAAR reading test fluctuated between 76 and 86 percent.

"The first thing we do is we try and fill in gaps one on one," Reyes said. "The teacher pulls [students] aside and works with them individually, uses the 1,000 words."

Reading specialist Gloria Reyes said Helwig's arrival brought a different feel to Graham. | Gabriel C. Pérez

Reading specialist Gloria Reyes said Helwig's arrival brought a different feel to Graham. | Gabriel C. Pérez

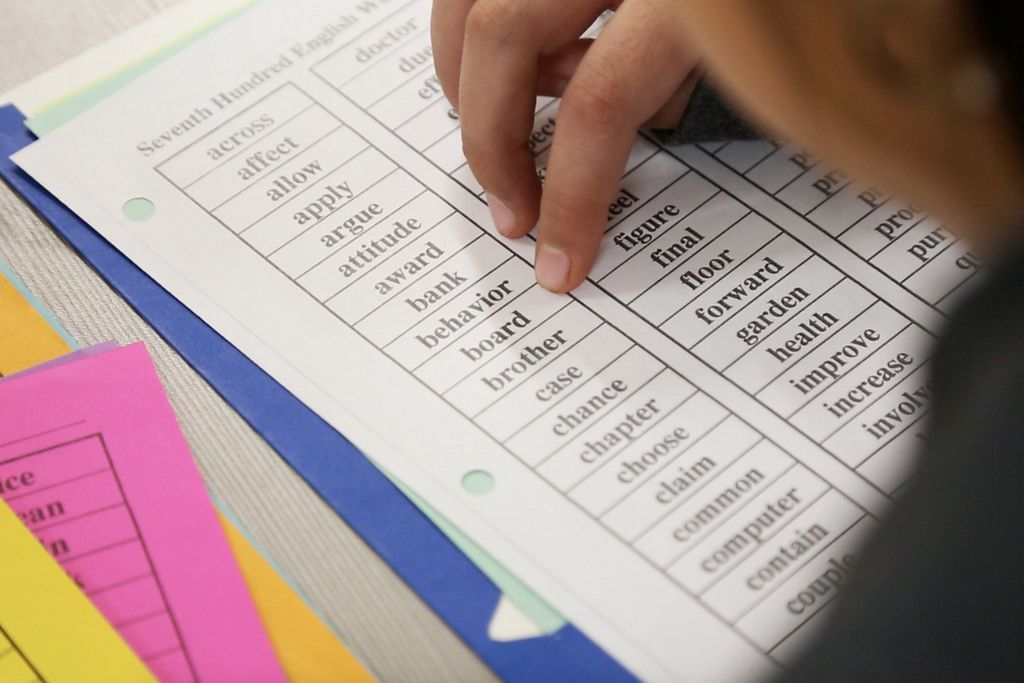

The "1,000 words" refers to a list Helwig created of the most common words in the English language. The words are divided into groups of 100 and get increasingly harder as a student moves through the list. The list helps students memorize certain words that don't follow the rules of phonics.

Helwig also made sure the school's culture centered around reading. Multiple teachers KUT spoke to said he allocated a lot of money for books the kids were interested in. The school expected students to be reading during downtime or waiting for their next class.

Reyes said Helwig and the teachers monitored all this.

"We had to turn in scores on a weekly basis," she said. "We had a graph [that showed] where the children were with their 1,000 words, where they were with their math progress. So there was constant having to turn in data and then review of that data."

By tracking how students did each day, teachers could catch when one started to fall behind.

This was a major shift in day-to-day operations. Expectations for both students and teachers were much higher. After Helwig explained his plans and made it clear every teacher had to participate, Reyes said, some teachers left. But others liked the changes.

Some parents did, too. Pete Vallejo was one of them. He sent his daughter to Graham when she came to live with him full time.

Pete Vallejo said Graham Elementary held him accountable for his daughter's progress. | Gabriel C. Pérez

Pete Vallejo said Graham Elementary held him accountable for his daughter's progress. | Gabriel C. Pérez

"She was behind [in fourth grade] for whatever reason with her mom, and she got here and they figured out where she needed help, what she needed to focus on and that's what they did," he said. "They also held me accountable with helping her out at home."

Vallejo said he and his daughter worked hard. Helwig would call and give updates on how she was doing and when she was falling behind. When spring came, Vallejo said, he was worried she wouldn't pass the STAAR test.

But then he got a call.

"[Helwig] said, ‘I have some news,'" Vallejo said. "I went to the school, he pulled me in the office and when he said she passed, he gave me a hug, and I actually cried because it was an emotional moment. A big old guy like I am, I don't show much emotion, but I broke down that day in his office."

Vallejo's daughter wasn't the only one to improve dramatically in a short amount of time. The year before Helwig started, 82 percent of students passed the reading test. Scores ticked up a little after his first year, but by the second year, 96 percent of students passed.

In just two years, Graham students were performing as well as students on the other side of town, where there was little poverty. And district data obtained by KUT show Graham students continued to do much better on state standardized tests compared to students from other low-income schools.

The 1,000-Word Challenge

When Helwig saw that his strategies were working, he started sharing them with other administrators.

"He sent out this blanket email to administrators across the Central Texas area just randomly, with … stuff," said Malaki Hawkins, who was principal of Manor Elementary School at the time. "So when I was looking at this I was like – Who sends out free stuff like this? Who does that?"

When she got the email, she was trying to find a way to boost her school's mediocre scores. Manor's demographics were similar to Graham's, so seeing Helwig's success impressed her. She said she appreciated that the program was easy to implement, and she liked the 1,000-word list because she knows how important vocabulary is.

Malaki Hawkins, the first principal of Lagos Elementary in Manor ISD, adopted Helwig's reading philosophy. | Gabriel C. Pérez

Malaki Hawkins, the first principal of Lagos Elementary in Manor ISD, adopted Helwig's reading philosophy. | Gabriel C. Pérez

"If students don't understand vocabulary or have a good understanding of vocabulary and how that builds comprehension, it's going to be a battle by the time they get to fifth grade," Hawkins said, "because they never did learn some basic key elements of reading."

So when she was hired to be the first principal of Lagos Elementary in Manor ISD, she brought this reading philosophy with her. She talked with Helwig about his tactics and adopted them.

One of the people in charge of running the program at Lagos is Pamela Gray, who followed Hawkins from Manor. She said the school saw improvements in reading scores and other areas.

"Discipline was better, because the kids weren't as frustrated because they could read these basic words – especially our [English-language learners]," she said. "Just by learning the 1,000 words, they were doing better in classwork."

The 1,000-word challenge starts in pre-K. By the end of kindergarten, kids are expected to know how to read, spell and understand the meaning of the first 100 words. In first grade, it's the first 600. From each grade after, they are expected to master all 1,000.

Students in Megan Savarino's fourth-grade classroom practice words for the 1,000-word challenge. | Gabriel C. Pérez

Students in Megan Savarino's fourth-grade classroom practice words for the 1,000-word challenge. | Gabriel C. Pérez

Teachers at Lagos go over the meaning, pronunciation and spelling of 25 words or so every week. Gray spends her days testing students individually.

Testing is a huge part of the program. Teachers can't just go over vocabulary words in class and give spelling tests. Students must prove they have mastered the words.

In September, Gray took fourth-grader Kamila into the hallway to test her. She opened her folder, pulled out a piece of paper with the first 100 words, and set a timer for 95 seconds.

Kamila began reading.

Pamela Gray, a literacy coach at Lagos Elementary, tests Kamila on the 1,000 words. | Gabriel C. Pérez

Pamela Gray, a literacy coach at Lagos Elementary, tests Kamila on the 1,000 words. | Gabriel C. Pérez

She read through the first 100 words easily, then the second and third. Eventually, they turned to the last page in her folder.

"You know you're on your 10th list?" Gray said. "That means your last 100 words."

"It is?" Kamila asked.

"When you finish this, it will be 1,000!"

Kamila was the first fourth-grader that school year to master all 1,000 words. If she hadn't, Gray and her teacher would test her every week until she got it.

As a principal, Hawkins said one thing she appreciates about the program is the consistency. Every teacher is using the same strategies to get their kids reading on grade level. Hawkins said that helps students over the course of the six years they spend in elementary school.

"Versus having pockets of greatness, as I would call it," she said, "where you have this amazing teacher in this one grade level, but in the other grade levels, you have teachers that are struggling."

Gray said she sees how a first-year teacher and a veteran of 20 years can both implement these strategies and see kids improve. She said she thinks more schools should be using the program.

"I think Austin is ridiculous for not using it in all of their schools," Gray said. "And I regret that Blaine didn't get the credit he deserved, because this is amazing."

But in Austin ISD, the reading program – and Blaine Helwig – are extremely controversial.

'Drilling And Killing'

For almost a decade, Graham used these strategies, and its scores stayed high. Under Helwig's leadership, it was named a Blue Ribbon School by the U.S. Department of Education. The award is given to schools for progress in closing achievement gaps.

Blaine Helwig (center) accepts a Terrel H. Bell Award for Outstanding School Leadership from the U.S. Department of Education in 2012. He was recognized for bringing "student scores from 'barely acceptable' to exemplary in five years." | U.S. Department of Education

Blaine Helwig (center) accepts a Terrel H. Bell Award for Outstanding School Leadership from the U.S. Department of Education in 2012. He was recognized for bringing "student scores from 'barely acceptable' to exemplary in five years." | U.S. Department of Education

But it was never celebrated as a solution in AISD.

One reason, Reyes said: "Blaine was completely disliked."

Reyes, who retired last year, was the only educator willing to speak on the record. KUT talked to eight others who worked with Helwig, but none wanted to be quoted for job reasons. Helwig, who retired in 2016, spoke with KUT for months, but in the end, didn't want to be recorded out of fear of retaliation.

Before he came into education, Helwig was a structural engineer, designing bridges. He also has a degree in accounting. He's a numbers guy, Reyes said, so he focused on what data told him worked, not what the district told him.

"Blaine was completely disliked."

"I have to say, part of it is that Blaine is the type of personality of 'I'm going to do what's right and I don't care what you tell me,'" she said. "That rubbed a lot of people the wrong way. He doesn't play the game, and he created a lot of enemies that way."

This is how intense the pushback to his methods is: Last May, text messages from then-school board President Kendall Pace were made public. In the texts, she expressed frustration to another board member about the achievement gap and lack of effort to close it. She texted that the district should be using Helwig's methods at some of its low-performing schools.

Kendall Pace resigned as president of the school board following controversy after texts were released showing her support of Helwig's methods. | Jorge Sanhueza-Lyon

Kendall Pace resigned as president of the school board following controversy after texts were released showing her support of Helwig's methods. | Jorge Sanhueza-Lyon

That didn't sit well with the local teachers union, which held a press conference asking for her to step down.

The texts came out on a Wednesday. The following Monday, Pace resigned.

A regularly scheduled school board meeting was held that night. Half the people who signed up for public comment expressed outrage at Pace's support of Helwig's strategies. One of the most popular ways critics described it: "drilling and killing."

Pace's texts not only referenced Helwig, but also Betty Jenkins, his domestic partner.

Jenkins implemented his strategies as a principal at Blackshear Elementary. Blackshear's test scores skyrocketed, and the school earned a Blue Ribbon award from the federal government.

Jenkins brought the practice to other elementary schools. Most of the people speaking at the May school board meeting encountered these reading strategies at those schools. No one at the meeting was from the Graham community.

Deborah Trejo, an AISD parent who serves on multiple committees within the district, expressed anger about Pace's praise of Jenkins and Helwig.

"[They] are not literacy experts, but have paternalistically decided that at the most economically disadvantaged schools, the only thing that matters is short-term STAAR results," she said during public comment. "And students should be fed a grueling diet of daily test prep and weekly practice tests."

Community members slammed Helwig's teaching strategies at a school board meeting in May 2018. | Gabriel C. Pérez

Community members slammed Helwig's teaching strategies at a school board meeting in May 2018. | Gabriel C. Pérez

A common theme community members brought up was that schools take away other opportunities from students when they focus only on a test.

"Children's spirit, imagination, creativity, their ability to dream, the things that make them human and provide meaning are stifled and sacrificed in the name of the God of testing," AISD grad Rocio Villalobos said. "The same is true for teachers and their imagination and creativity."

Some speakers asked the board to stop practices like the 1,000-word challenge and instead focus on more creative ways of teaching, like project-based learning, a holistic method that requires students to work together using knowledge from multiple subject areas. Its aim is to teach communication skills and show students how what they learn in class applies to the real world.

Helwig would argue, however, students can't thrive in a more creative learning environment if they can't read at grade level.

An Emphasis On English

Another major criticism of Helwig's tactics is the focus on reading in English. A number of AISD schools – including Graham – have a significant number of students who enter not knowing the language. Graham was supposed to focus on both English and Spanish to help English learners transition. But instead, Helwig decided to focus only on reading in English to get kids on grade level.

"A good majority of these children do not have a strong Spanish vocabulary, cannot speak in complete sentences in their native language," Reyes said. "We felt it was better to go ahead and strengthen their English language."

Reyes and her husband raised their sons speaking both English and Spanish. She said she understands how beneficial speaking two languages is, but it's difficult to implement a strong dual-language program when schools face other demands.

"The reason they have to learn in English is when they leave elementary school, everything is in English," she said. "They are heavily textbook-oriented once they get to middle and high school. They have to be able to read them, and if they don't read in English, they likely drop out."

Lagos Elementary students study words for the 1,000-word challenge. | Gabriel C. Pérez

Lagos Elementary students study words for the 1,000-word challenge. | Gabriel C. Pérez

That's not the right way to look at children, said Trejo, who serves on multiple advisory boards for dual-language issues in AISD. She said abandoning dual language is harmful to kids.

"You say to them, 'I need to erase you. I need to erase your connection to your home, to your family, to all the language you know is not worth anything,'" she said.

Helwig found academic success at the cost of a student's home language, she said.

The Challenge Of Consistency

Last September, a coalition of people who advocate for schools in East Austin announced a list of demands of AISD. The group called the 15-item list a “manifesto” and said the district needs to do more to help low-income students and children of color.

The group said if the district didn’t lay out a plan for improving academics at East Side schools, it would sue.

Since then, AISD Superintendent Paul Cruz and the school board have publicly talked about how they can address the achievement gap. The way to do it, they say, is to make sure every student is reading by third grade.

"Every teacher would have training on the science behind reading," Cruz said. "That's something that’s been in play in several schools and several classrooms … but we want to make sure it’s systemic."

AISD Superintendent Paul Cruz says he doesn't want schools to focus just on strategies that provide academic success; he also wants them to teach students emotional skills. | Gabriel C. Pérez

AISD Superintendent Paul Cruz says he doesn't want schools to focus just on strategies that provide academic success; he also wants them to teach students emotional skills. | Gabriel C. Pérez

Cruz wants every elementary teacher in the district to know how to teach reading, which isn't always included in teacher-training programs.

To achieve this general goal, he’s proposed training for all first-grade teachers and hiring more advanced-reading specialists.

Right now, principals have a lot of autonomy over how they run their schools. That’s how Helwig was able to create a system of teaching and use it for almost a decade.

Michael Coyne, a professor of educational psychology at the University of Connecticut who studies literacy, said it’s challenging to mandate a blanket policy for a large number of schools.

"Yeah, it's easy to say that we want all kids reading by third grade, and we all agree how important that is," he said. "But sometimes I think we underestimate the level of support students need and the level of support teachers need to be able to approach that goal."

Those supports include frequent assessments to help teachers know when a kid is falling behind, he said, and effective tutoring and support for those who need it. Teachers also need ongoing training.

"It's easy to say that we want all kids reading by third grade. ... But sometimes I think we underestimate the level of support students need and the level of support teachers need to be able to approach that goal."

The most important part to all of that, Coyne said, is consistency. Even if teachers are providing excellent reading instruction, if they’re all doing something different it’s hard for students to build on their reading skills across grades.

That consistency will be a challenge for AISD. District administrators want principals to have freedom in how they run their schools and decide how subjects are taught. AISD can’t mandate that reading instruction be done a certain way.

Consistency is what Helwig provided at Graham. As long as a student stayed at the school, she would have teachers, reading specialists and a principal constantly checking in and intervening. The school didn’t allow kids to slide. Teachers said the goal was to make sure fifth-graders went on to middle school reading on grade level.

The practice worked so well at Graham because everyone was on board and participated. If the district tried to mandate all schools replicate it, there would be no guarantee of buy-in from every principal and teacher.

Testing Vs. Creative Learning

This brings up a philosophical question many in education wrestle with: Should school time be focused on getting students to pass a test or spent learning in creative and collaborative ways?

AISD leaders face this question every day. When certain groups of students are doing so poorly on the STAAR test, they can't ignore it.

"We have achievement gaps. We see it in our data," Cruz said, referring to STAAR scores. "We have parents, community members talking to us about this achievement gap."

While the STAAR scores concern Cruz, Gilbert Hicks, associate superintendent for elementary schools in AISD, recognizes where teachers are coming from. A test score doesn't define a student.

"It's really painful for me to see someone think a score that comes out of that day is the end-all be-all for a student," Hicks said. "It's a number, and we have to accept it on that particular day, but there might be other variables."

The state and federal government say kids have to take these tests, and if they bomb them, the school faces consequences. In Texas, the state can take over an entire school district if multiple schools are underperforming.

It's a tricky situation for school districts; nobody wants to rely on a test score to determine whether a student is successful, but test scores are the only objective measure to gauge how schools are doing.

Helwig developed his reading plan in this environment, where test scores mattered. The former engineer saw a problem and found a way to fix it.

"It's really painful for me to see someone think a score that comes out of that day is the end-all be-all for a student."

When asked about the methods and success at Graham and Blackshear, Hicks said it was incomplete, but he did like one aspect.

"You would also go and see novel studies occurring, where those strategies were being learned or applied in a more holistic way," he said. At Graham, teachers used novels – rather than short passages – to help students practice their reading skills, and they said it kept kids engaged.

Cruz said he doesn't want AISD schools to just focus on strategies that provide academic success; he also wants them to teach students emotional skills and how to work together.

Neither Cruz nor Hicks would say whether they would recommend other schools try Helwig's tactics as a way to close the achievement gap.

What's Next?

With mounting pressure to improve academics, implementing methods like Helwig's would seem attractive.

Yet his strategy was unpopular. Too many people think it celebrates the wrong thing – valuing testing over creativity. And in education, politics and public opinion matter.

In the end, Austin is a good case study for why the achievement gap is so hard to close in American schools. Millions of dollars have been spent, dozens of studies have been done, and yet the problem remains. Schools are set up as a patchwork, where principals have the freedom to create their own education environment.

For now, the district is opting for teacher trainings and more reading specialists. Will that be the answer?

We'll see.

Listen to Claire McInerny's 30-minute documentary: