Love Letters To An Empty Austin: One Year Later

At the start of the pandemic, KUT asked listeners to write love letters to their city. They shared what they missed about Austin — live music, festivals, bars and restaurants. And their grief.

“Walking into an empty school building is one of the saddest parts of all of this,” wrote teacher Brooke Maudlin. “My students deserve bright classrooms and smiling teachers and now that school experience is gone.”

It’s been a year. The city has lost more than 800 people to COVID-19, longtime businesses have been forced to close and many students have yet to step foot in a classroom again.

Austinites are still missing live concerts and crowded celebrations and an overall feeling of normalcy. We checked in with some of those who wrote love letters at the start of the pandemic to see how they’ve adapted over the last year — and what they’re still grieving.

Watch their original love letter videos and read updates on their lives below.

Brooke Maudlin, teacher

Brooke Maudlin teaches Spanish at Akins High School in South Austin. Her days somewhat resemble pre-pandemic life: She goes into her classroom each morning and heads home to her family in the evenings. But seven months into the school year, she still hasn’t met most of her students in person. A few come into the classroom to learn in person, but most have opted for lessons through Zoom.

“I am still teaching through a computer every single day,” she said. “It’s been unlike any other school year, and it’s sad. I miss the normal interactions, but I think we are making the most of it with what we have. And most of the kids are keeping up the best they can, but a lot are struggling and are falling through the cracks.”

Maudlin misses the events and family traditions that haven’t been possible — Eeyore’s Birthday, Blues on the Green and the numerous marathons that take over city streets each year. Before the pandemic, she was excited to bring her daughter, now 3, into the traditions she and her husband always look forward to.

“It's like she's missing out on the things that are uniquely Austin,” Maudlin said. “This is part of our culture. This is part of our family traditions. And all of that got brought to a halt. She's young enough. There'll be more opportunities, of course, in the future. But I think I was just super excited that, ‘Oh, I have a kid now that I can dress up and bring to these festivals and do all these things.’”

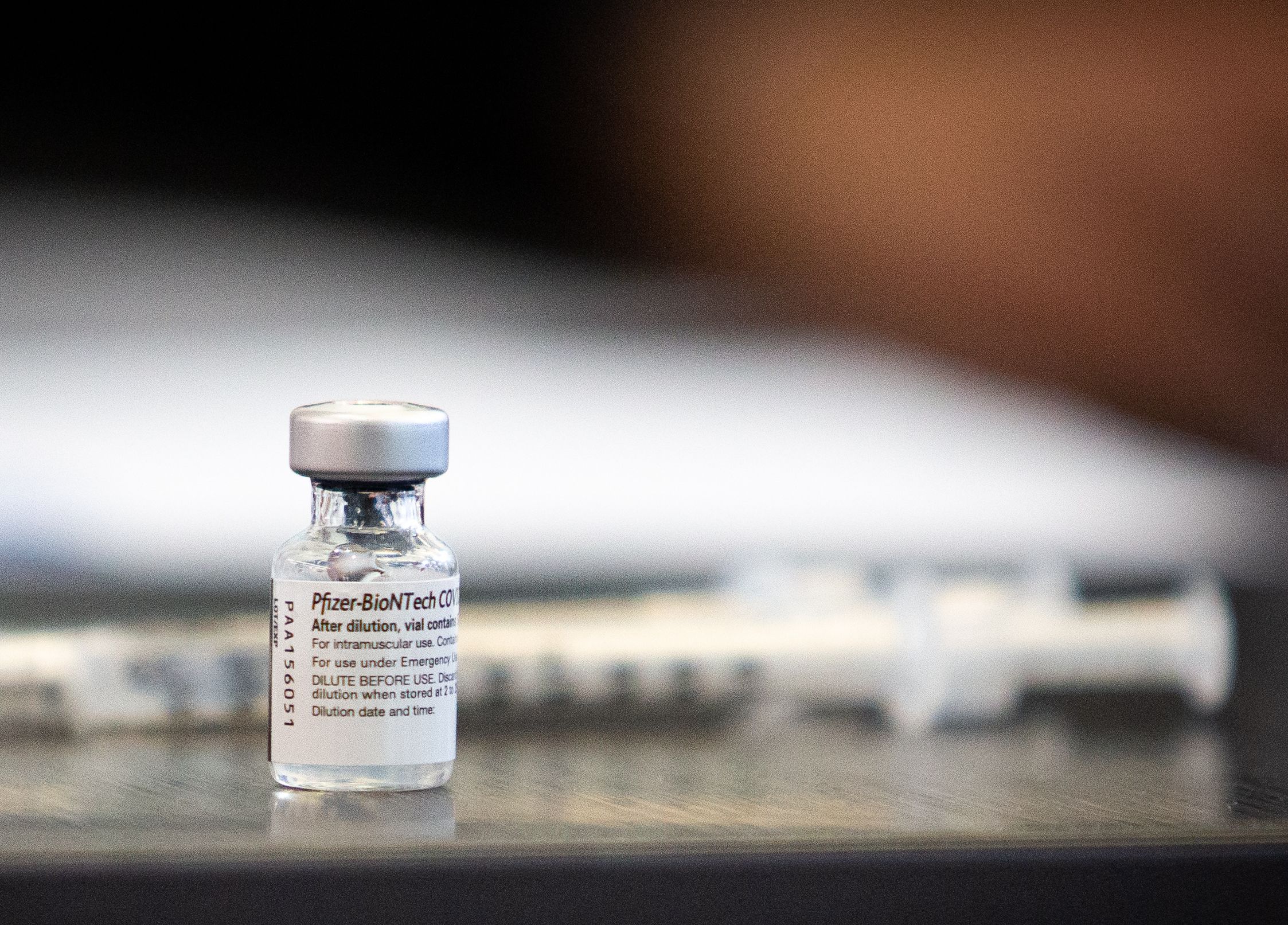

In her original letter, Maudlin said: “Don’t worry, Austin. I know we’ll be back.” And she still feels that way. The vaccines give her hope. She’s getting her second dose on Easter Sunday.

“If I were to rewrite a letter, I would probably say: ‘Oh my God. Can you believe we just did that for a year?’” Maudlin said. “‘We’ve got a lot to make up for — so who's coming over first?’”

Merga Gemeda, taxi driver

On March 17, 2020, Merga Gemeda sat in his taxicab in the parking lot of a Dollar General store, waiting for his phone to ring. By 1 p.m. that Tuesday, he had given only one ride. Gemeda found himself grappling with the new reality taking shape around him as the first week of lockdown in Austin began. He realized a disheartening fact: He may have to take a break from driving his taxi.

“Right now, our business is really down by probably 90, 95 percent,” he said at the time. “There is no way of surviving in this situation. I don’t know what to do. … I don’t have another job.”

At 62, he worried both about health issues and his source of income.

The next day, he surrendered his meter. In the following months, he applied for unemployment and decided to stay at home indefinitely. He and his wife adjusted their lifestyle to keep expenses down.

In his original love letter, Gemeda said what he missed most about his job was making new friendships with his customers and exploring the city.

“It is in this time that I most miss all of the relationships I built,” he wrote. “We created a bond akin to close friendship – family, in some cases. I miss making a living by making friendships.”

More than a year later, Gemeda still has not gone back to taxi driving. But he has maintained friendships with his favorite customers.

“A lot of them – I have it on my text [messages] – they say that they miss me. And I say I miss them, too,” he said. “Even from Florida, from Austin, from everywhere. They want to check how I’m doing and I want to check how they are doing.”

Gemeda cherishes these message exchanges as he awaits his second dose of the vaccine. After that, he will decide if and when he will return to the road.

John Lawhon, postal worker

Over the last year, people have seen fewer friends, family members and co-workers. But for some Austinites, John Lawhon remained a constant familiar face.

He’s worked at the post office on East Sixth Street for the last eight years, often chatting with regulars — something he’s kind of known for.

When the pandemic hit, he didn’t stop going into work. In fact, his workload increased as more and more people turned to online shopping.

“If they have to run and get something, they don't do that anymore. They just order online,” he said. “I thought it was going to be a slowdown, but instead it just sped up and probably it's double or triple the amount of work that we get now as opposed to a year ago.”

He soon found that people were hungrier for social interaction than normal. They weren’t doing typical activities, like going to concerts or bars and coffee shops, but they still had to go to the post office.

“A couple people told me, they would exclaim, ‘Yay, you’re the only person that I’m going to be talking to or having a conversation with for the next year,’” Lawhon said. “You know, because they’ve decided they’re going to go in the house and stay in the house, only come out to go to the post office or [take] very few trips out.”

He says he feels lucky he’s been able to maintain social interactions throughout the pandemic, because of his job. But he knows not everyone has been so lucky. And people are tired – tired of social distancing and other precautions they’ve been asked to take over and over again.

Lawhon wrote a second love letter to Austin in March 2021.

“People are still wearing a mask; I see everybody wearing a mask,” he said. “But I can tell they’re just exhausted, you know. They’ve been put through the wringer.”

Lawhon recently watched a movie he hadn’t seen in a while, “Into the Wild.” It’s based on the story of Christopher McCandless, a man who gave up his possessions to live alone in the wilderness. A line McCandless scribbled before he died struck Lawhon as something a lot of people have probably been feeling: “Happiness [is] only real when shared.”

“I don't know if I agree with that fully,” he said, “but the premise is like your life isn't validated until you can really share it with somebody else, you know?”

Taylor Henderson, small-business owner

When the world went into lockdown, Taylor Henderson panicked. As the owner of Flavors Creative Group, a small clothing retailer that sells at pop-up shops and community events, he wondered how the business would survive — let alone how he would.

“I was kind of frantically anxious,” he said, reflecting on March 2020. “How would I sell clothes?” He worried sales would dwindle as people experienced job loss and financial uncertainty during a pandemic that had no end in sight.

Then he noticed a shortage of face masks. He saw smaller companies starting to put their resources into making them.

“And people were responding,” he said. “People needed this item.”

He and his business partner picked up some scrap fabric and began engineering several concepts, finding the most efficient and sustainable way to make them.

They released their first 20 – selling out in two minutes.

“And so from there we knew we had an idea,” Henderson said.

Flavors ramped up production to 20 to 25 masks per day, and tried to keep the price affordable at $12 each. He wanted the masks to be accessible to people who needed them for their livelihoods, especially essential workers.

The masks quickly proved to be a way to both pay rent and fill a need in the community. They also boosted Flavors’ reputation as a local brand and became the company’s top-selling item in 2020.

“As I reflect on it, I’m just thankful that we really got in when we could,” Henderson said. “I think people really needed it and responded to it in the positive manner we were hoping for.”

Arturo Silva, architect

When Arturo Silva moved to Austin from Mexico five years ago, he fell in love with the city — the lake, the parks, the bike trails.

But when the pandemic hit, he had to find new activities to do at home. Silva, who works at an architectural firm in Austin, found an upside: The pandemic encouraged universities to create more online offerings. So, he signed up to take architecture classes online from the University of Mexico.

“The pandemic gave me the opportunity to do that,” Silva said. “That is one of the great things I discovered that I can use my time right now taking classes.”

In his original love letter, he wrote, in Spanish, “Now we enjoy nights more. Stars shine in the vastness of space, and they remind us that we will come out of this together, that the days will return when we can enjoy the secrets you still have saved for us.”

He’s still optimistic about the future. More than a year later, he hopes his fellow Austinites can hold on a little longer and keep wearing masks and staying safe.

“And if you are allowed to take the vaccine,” he says, “take it.”

Paula Wilson, nurse

Paula Wilson started the pandemic on the frontlines, before anyone knew what that responsibility would entail.

“I think a lot of the people I work with were scared, and nobody knew what we needed to do to stay safe,” she said.

As a nurse practitioner in neurosurgery at Ascension-Seton, Wilson needed to find a balance between being there for her patients and keeping her family safe. With limited personal protective equipment in the beginning, she and other medical staff found themselves using makeshift gear.

“We just had to make do with what we had,” she said.

She started taking on night shifts, so she could work around fewer people.

“It was a sort of self-chosen isolation,” she said. “I was so scared of COVID, I would remove all my clothes in the garage when I came home. I would shower as soon as I came home, would stay away from my family. I slept in a separate room from my family. And any time I saw any patient with COVID, I stayed away from my extended family for two weeks.”

Her life became an ongoing mental math equation, carefully calculating isolation periods and weighing possible risk against the need for time with her children.

“We just kind of acted like they may have also been exposed if I was exposed,” she said.

Being in the hospital was a different kind of challenge. Wilson watched COVID-19 patients go through sickness alone, since they weren’t allowed visitors.

“It’s tough to see people dying alone,” she said. “And to explain to somebody how to try to say goodbye to somebody, to their loved one, over video is impossible. And I still don't know a good way of doing it. I don't know that there will ever be a good way to do that.”

Over time, Wilson and her family adapted to this new life. During her time off, they turned their family time together into a chance to explore more parks around Austin.

“One of the things that my daughter pointed out last summer was that we've never spent this much time together as a family,” Wilson said. “Our schedules were always booked every day. My kids, even though we live in the same house, always had different activities, always had something going on, and had just never learned, I guess, how to just be together all the time.”

Wilson said her children have discovered new interests, like hiking and being outdoors.

“They're really great together. They’ve learned to work together as this little team,” she said. “That's really been an amazing gift.”

Wilson now has a new position at work, better hours and a vaccine. As the vaccine rollout continues, she remains hopeful that life will soon feel safer.

Kalu James, musician

As a musician in the Live Music Capital of the World, the idea of playing just four shows in the span of one year would have been laughable before 2020. But that was the reality for Kalu James of the band Kalu and the Electric Joint.

“Up until the pandemic, I probably played four shows sometimes in a week,” James said.

Like other musicians in Austin, he felt disoriented as iconic music festivals and historic venues shut down with the onset of the pandemic. Without live shows and guaranteed revenue, being a musician anywhere looked bleak.

But James decided to view quarantine as an opportunity.

“I've written a lot more this year than I’ve written in a long time,” he said. “I've gotten the chance to, you know, go through my voice memos and pick up all these songs that literally have just been sitting there and waiting for the time to be unearthed again.”

Without shows, travel and the normal business of life, he has learned to sit alone in his small studio apartment and become more comfortable with himself.

“It’s just been me and my little plant that I named Pretty Pink,” he said.

In that space, he’s found new creativity.

“There're a lot of emotions to process in so many different ways,” he said. “And it's been amazing to be able to put that in songs.”

Some of those emotions are about his loved ones back home. Born in Nigeria, James has worried about being able to travel to see family in West Africa. His mother, who lives in Benin, finally was able to visit this winter. She got vaccinated in the U.S. just before returning home.

“It will be much harder [for her] to do that back home,” James said. “It’s just really important to me to try to do whatever I can for her.”

Just as things started feeling more hopeful, Pretty Pink lost all its petals during the winter storm in February. James views this as a metaphor for the complicated process of moving forward.

“It’s just that whole idea of healing. It’s not linear,” he said.

Outside his apartment, the world is going through its own ups and downs. South Congress Avenue, which James described feeling “like the 3 a.m. of a Monday morning” in his original love letter, now teems with open businesses and people at various stages of vaccination.

“People are trying to do the best they can and, with all things considered, move forward,” he said.

And so is James. Inside his apartment, he writes music, prunes Pretty Pink back and makes hopeful plans to play more shows than he did last year.